ETQ-AI Data Collection App

Classroom observation is expensive, subjective, and logistically difficult to scale. In Germany, high-quality teaching feedback is constrained not only by cost, but also by strict data protection law and institutional trust requirements.

In the ETQ-AI (Enhancing Teaching Quality with Artificial Intelligence project, our goal is to automate parts of teaching quality assessment: record classroom discourse, transcribe it, and use LLMs to score dimensions such as classroom management and student cognitive engagement. The long-term vision is simple but ambitious:

What sounds like an ML problem quickly became a systems, privacy, and deployment problem. As the technical lead and product owner for ETQ-AI data collection app, I owned the full product lifecycle — from system architecture and GDPR compliance to managing the development team. This post details how I bridged the gap between academic ML prototypes and a robust, privacy-first production mobile app used in real German classrooms. Coming from an academic background, a summary of lessons I learned in this applied projecct are:

- Deployment metrics differ so much from benchmarks.

- Privacy requires system-level handling.

- Model failures can/must be handled architecturally.

- Infrastructure decisions significantly influence timelines.

- Ownership means maintaining coherence.

Let’s dive deeper into my project!

1. The challenge: beyond the model

The core research question was automated teaching quality assessment: can automates speech recognition (ASR) + LLMs replace human raters?

Signal

Recognition

when

Diarization

Model (LLM)

Quality Scores

However, to answer that, we first needed a reliable data collection pipeline. We needed recordings from real classrooms with parental consent, strict GDPR compliance, and a format researchers could actually use. We also needed a user-friendly tool that teachers would actually want to use.

I acted as the bridge between research requirements and engineering reality. My role involved:

- Product management: Defining the scope of data collection, roadmap, and user requirements.

- Technical architecture: Designing the end-to-end data flow and making trade-offs between privacy, latency, and model accuracy.

- Team leadership: Managing two student developers (Usman Amjad and Nitin Jain) who implemented the Flutter frontend, and a PhD student (Puja Maharjan) who buit the ML pipeline.

- Stakeholder management: Coordinating between project members and teachers, and translating legal requirements into technical specifications.

2. Starting simple: the recording interface

The app’s core function is straightforward: record audio, transcribe it, let the teacher review and upload.

Login supports email and Google authentication. We deliberately don’t collect any personal data at this stage. The main screen is minimal: a record button and a list of past recordings. This simplicity was intentional — our users are teachers in the middle of a workday, not power users.

3. GDPR shaped the architecture

Working with classroom audio in Germany means working under GDPR, and this constraint influenced almost every design decision.

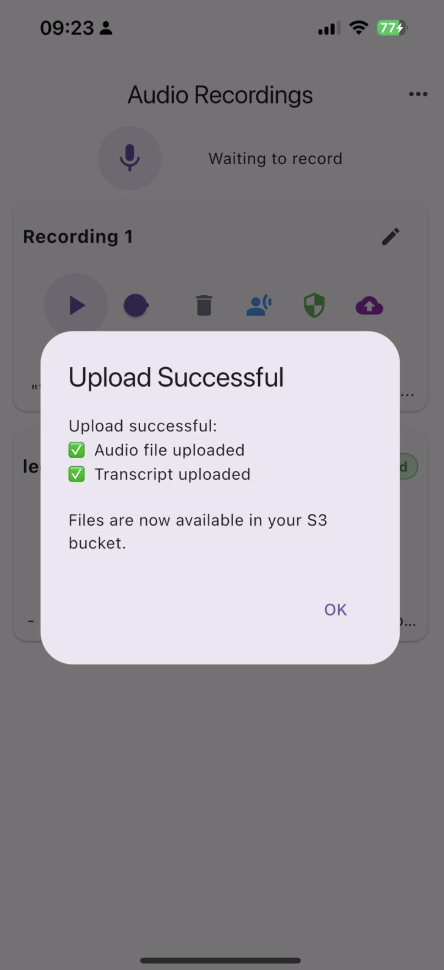

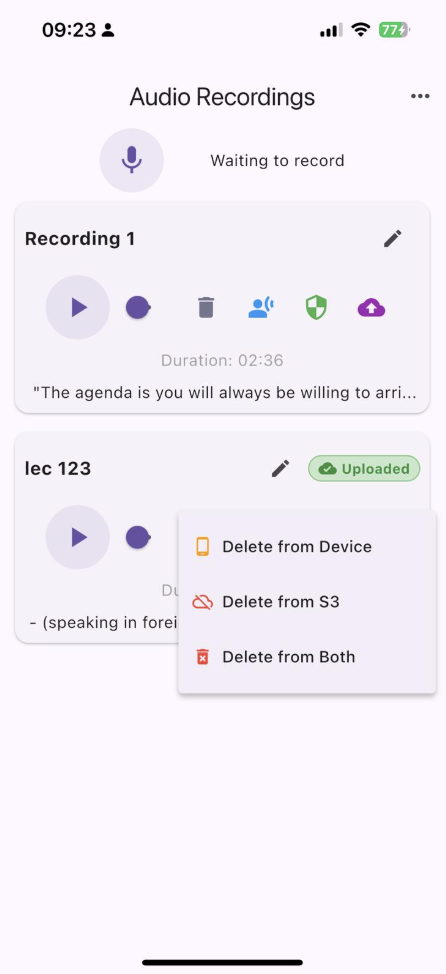

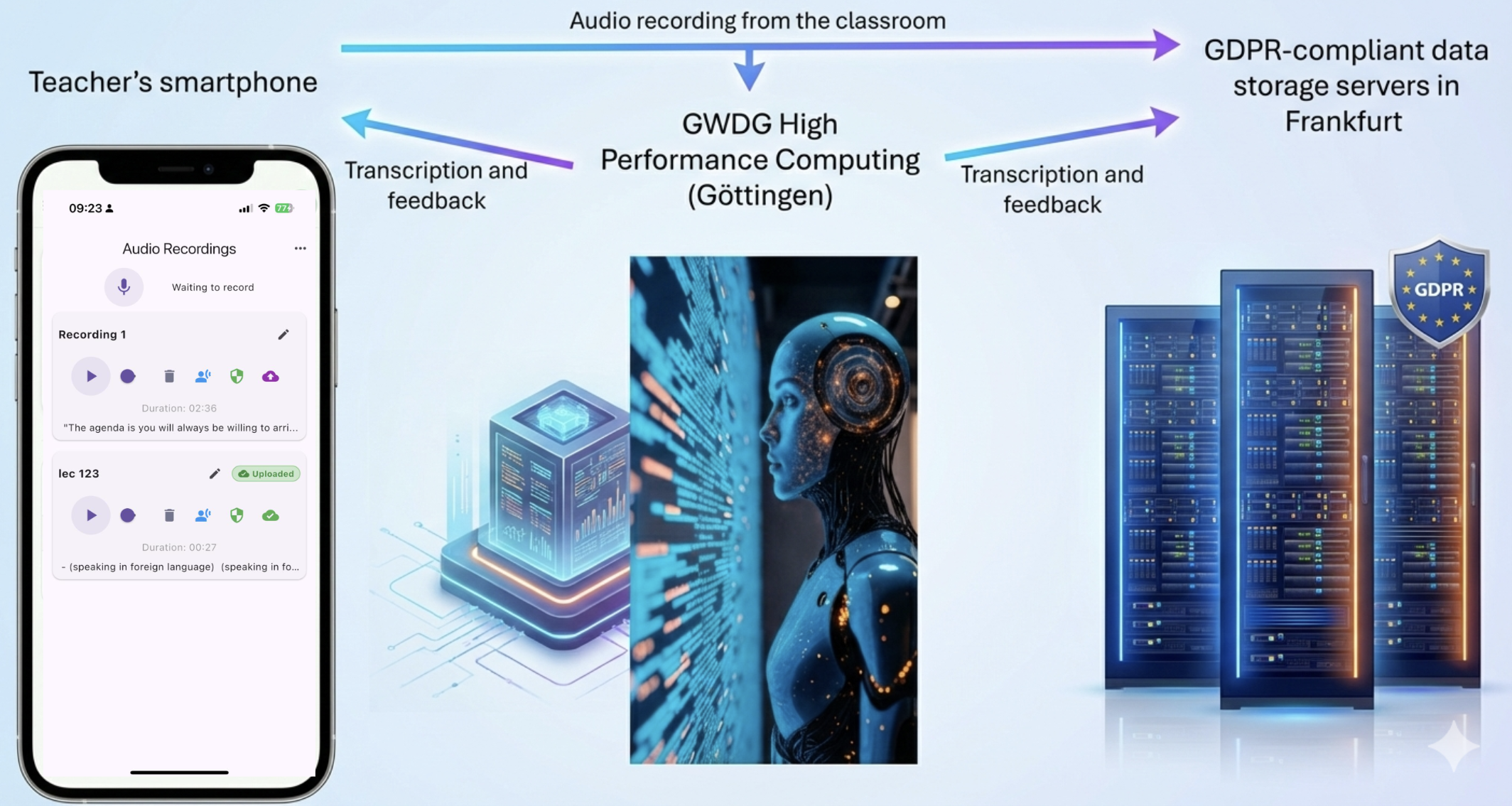

We, as researchers, need data on a server to run experiments, but teachers (and students’ parents) need to trust that their data is handled properly. We landed on a design where personal data stays on the teacher’s device by default, and upload to our research servers is an explicit, separate action. The teacher can review the transcription before uploading, and can delete data from the device, from the server, or from both — independently. We also added a full account deletion option: one tap removes all associated data everywhere. This sounds simple, but implementing proper cascading deletion across device storage, cloud storage, and authentication records required careful coordination.

Infrastructure strategy: We store uploaded data on Amazon S3 servers in Frankfurt (eu-central-1) to ensure that the data stay within the EU. However, for transcription, we utilize high performance computing (HPC) servers at Göttingen. Separating storage (Frankfurt) from compute (Göttingen) was a strategic decision I made after mapping the data governance capabilities of each site. GWDG offered the necessary GPU power but was only authorized for transient processing, while AWS provided the compliant long-term storage we needed. Orchestrating the alignment between these sites was a key non-technical challenge I solved.

4. Real world deployment challenges

This project taught me quite a bit about the differences between ideal academic research and real world deployment. Here are some examples:

4.1. On-device transformers didn’t survive contact with reality

Our initial plan was quite fun: running Whisper on-device for transcription so that classroom audio never needs to leave the teacher’s phone at all. Maximum privacy, minimum infrastructure.

To make this work, we built on whisper.cpp, a C/C++ port of Whisper optimized for local, CPU-based inference on resource-constrained devices. By stripping away Python/PyTorch dependencies and relying on low-level GGML tensor operations, it can run substantially smaller model variants directly on a smartphone without GPU acceleration. To integrate this into our Flutter app, we used flutter_rust_bridge, which auto-generates the FFI (Foreign Function Interface) bindings between Dart and Rust. On the Rust side, whisper-rs wraps the raw C API of whisper.cpp, giving us a safe interface. The resulting call chain became Flutter UI → Dart → Rust → whisper.cpp (C/C++).

We tested several Whisper variants. On a typical smartphone, only tiny, base, and small were feasible in terms of memory and latency. But because their transcription quality isn’t great, we turned to server-side transcription via API calls to HPC servers, where we could run large-v3 and large-v3-turbo. The accuracy difference was substantial. This meant the audio does travel to a server for transcription, which we handle by requiring explicit user consent and ensuring the audio is processed transiently (not stored on the transcription server).

Lesson learned: on-device ML is great for demos but is often impractical for production because of the limitations of mobile hardware.

4.2. Academic vs real-world benchmarking

We benchmarked a range of ASR models on both standard datasets and our own classroom recordings. The gap was stark. Even the best-performing models — Voxtral-Mini-3B-2507 and Whisper-large-v3-turbo — achieved word error rates (WER) around 0.64–0.66 on student speech and 0.28 on teacher speech. On standard LibriSpeech benchmarks, those same models score 0.02–0.07. That is roughly a 10× degradation in accuracy when moving from clean, studio-recorded speech to a real classroom.

Student speech was consistently harder than teacher speech, largely because of microphone placement: a phone sitting on the teacher’s desk captures the teacher clearly and students at a distance, often through background noise. Beyond microphone distance, classrooms introduce overlapping speech, scraping chairs, background noise, and code-switching between German and technical vocabulary — conditions far removed from the clean audio that most ASR training sets are built on. The training data for most of these models isn’t public, but the distribution shift is evident in the numbers. One notable case is that NVIDIA’s Canary-1b-v2 achieves an impressive 0.021 WER on LibriSpeech English, yet collapses to a WER above 1.0 on student classroom. High benchmark scores are simply not predictive of classroom performance.

4.3. Output repetition issue

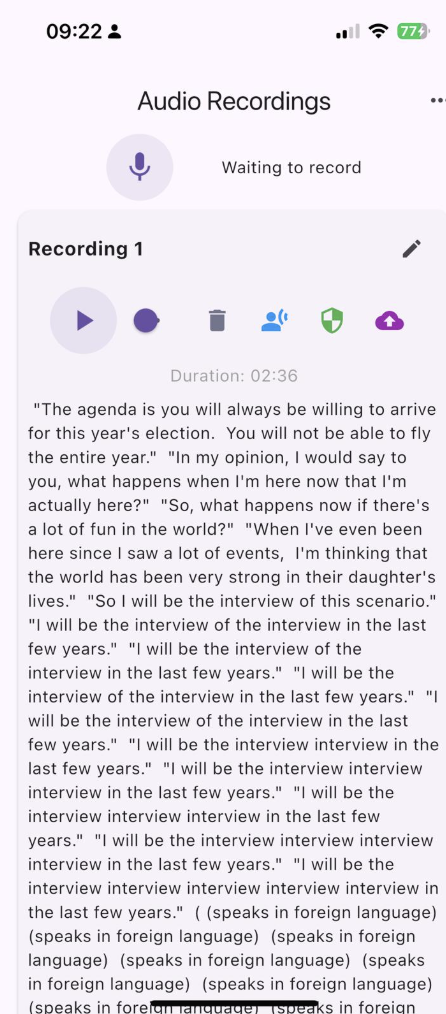

We also discovered a surprising failure mode: models keep repeating incorrect transcriptions for dozens of times! We show an example below, where we transcribe a random audio from YouTube:

It’s impossible to pin this down to a single factor, but our manual inspections show that such hallucinations occur when the words are not clear, and grow significantly with audio duration — especially with noisy or multilingual input. The fix was to chunk the audio into ~30-second segments before sending each to the transcription API, then stitch the results together. We discovered that WER rises steeply with segment length across all models, roughly doubling as segments grow from 30 to 300 seconds. The 30-second sweet spot is short enough to avoid hallucinations while long enough to preserve context across sentence boundaries.

But chunking introduced its own engineering challenge: the segmentation and sequential API calls need to happen in the background while the teacher continues using the app. In Flutter, managing background and foreground processes properly is non-trivial, especially on iOS where background execution is tightly restricted. We spent more time on getting background transcription reliable than on any ML-related problem.

4.4. Audio recording: deceptively hard on mobile

Another “should be simple but isn’t” problem is continuous audio recording on a mobile device. We discovered that recording stops abruptly when the user switches to another app, when the screen times out and goes black, or when the phone enters power-saving mode. For a teacher recording a 45-minute lesson, this is a not acceptable.

The solution requires properly implementing background audio services — registering the app as a background audio provider, handling lifecycle events, managing the audio session correctly. On Android this is manageable; on iOS (where Flutter’s background execution support is more limited), it required significant workarounds. This is the kind of platform-specific systems engineering that you never think about when you’re designing a pipeline in a Jupyter notebook.

5. What I would do differently

- Start with deployment constraints: We initially assumed transcription would be “good enough.” It wasn’t. Downstream components must be designed around noisy, imperfect inputs.

- Budget 3x more time for platform-specific issues: Mobile OS constraints consumed more engineering time than all ML components combined.

- Design for the user’s worst moment: If recording fails once during a 45-minute lesson, the tool loses trust. Reliability outweighs sophistication.

6. Transferable lessons for applied ML

This project changed how I think about applied machine learning:

- Benchmarks are not deployment metrics Leaderboard performance does not predict out-of-domain robustness.

- Privacy is a systems problem: GDPR influenced storage location, compute separation, consent flows, and deletion logic more than model choice did.

- Model failures can be handled architecturally: Repetition hallucinations were mitigated through segmentation and orchestration — not model fine-tuning.

- Infrastructure decisions dominate timelines: Background execution, mobile OS constraints, and data governance consumed more effort than training experiments.

- Ownership means maintaining coherence: Keeping architecture, user needs, compliance, and research goals aligned required explicit technical leadership.

7. The broader takeaway

Building ETQ-AI data collection app taught me that the interesting engineering problems in applied ML are rarely about the models. They’re about the system around the models: how data flows, where it’s stored, who controls it, what happens when the model fails, and how to make it all invisible to the user. This is the kind of work that doesn’t produce papers but determines whether a research prototype becomes a usable tool. It’s also the lens I now bring to research problems more broadly: not just “what’s the best model?” but “what does it take to make this actually work?”

ETQ-AI is a joint project between the Hector Research Institute of Education Sciences and Psychology and the Cluster of Excellence “Machine Learning for Science” at the University of Tübingen. The app was implemented by Usman Amjad and Nitin Jain.